BY AATISH NATH

To visit a fish market in Japan is to be allowed to view a choreographed performance, in which people become actors, each on a quest for the biggest, best seafood that money can buy. As a food writer, I was excited to sample fish in all its forms in a country known for its vaunted perfectionism. A visit to the auction though, was an opportunity to see the variety of seafood that’s caught, and a glimpse into the orderliness that permeates all aspects of Japanese society.

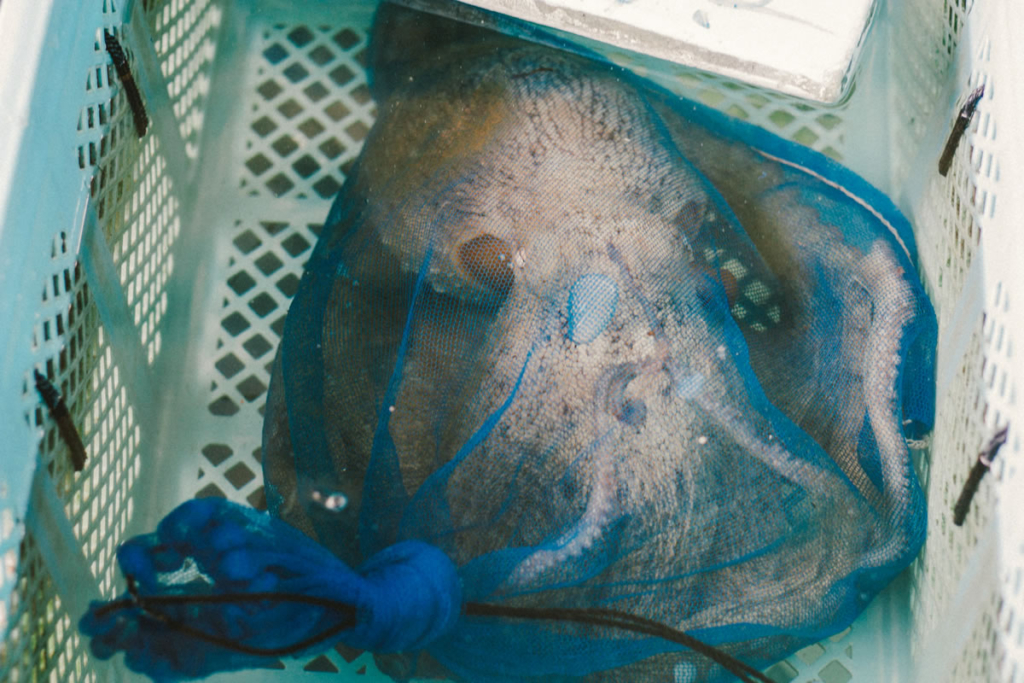

So, I was there to see some of the fish stored in neat rows of plastic bins, each with pipes circulating water through them. The makeshift tanks are filled—some with a single dangerous pufferfish (known as fugu in Japanese, which needs to be prepared with care, as it contains tetrodotoxin, a poison that is at least 200 times deadlier than cyanide), others with a shoal of mackerel (saba), their oily skin glistening in the tube lights reflected in the water, and walking further down octopus (tako), bagged in netting, so that their eight legs don’t find a way to escape the shallow tanks.

I was on Toshi-jima (jima means island in Japanese) an island in the Mie prefecture, to get a sense of coastal living in Japan. The closest city to the island, Toba is about three hours from Osaka. The small market may be serving only some of the 2,500 odd people on the island, but there’s still a sense of urgency in the air when it comes to bidding for the seafood.

Like all of Japan, there’s no unruliness, but instead, a carefully conducted ritual. I’m interrupting the flow of the day, and it makes me thankful that there’s a school field trip taking place at the same time that I am there, as they run around the tanks while I try to be the more measured disrupter, walking slowly from tank to tank, studying the fish on display.

The language barrier means that it is tougher to learn about the fish, and how to eat them, but that disappointment soon fades, as the auction starts. Participating in the auction is the ryokan owner’s wife where I am staying, and it’s thrilling to see the fish that I will be eating for dinner, being purchased and loaded into an open top van at the end of the auction. There’s no fugu on the menu, but as the day comes to an end, I partake in a kaiseki meal that features mackerel and more.

在日本,參觀魚市場等同於觀看一場精心設計的表演,在這個舞臺上,每一位搜尋著錢所能買到的最大、最好的海鮮的人都成為了演員。作為一位美食作家,能在這個以完美主義自誇的國家嘗試各種魚類,我感到十分興奮。參觀魚市拍賣既是一次得見捕撈海產豐富性的機會,又能一瞥日本社會方方面面的秩序井然。

在這裏,魚被儲存在整齊的塑料箱裏,每個箱子都安有水循環裝置。這些臨時的水箱都被裝滿了,有的只單獨放了一只河豚魚(日文叫 fugu,由於其中含有致命性至少是是氰化物200倍的河豚毒素,需要小心料理)其他的則放滿鯖魚,它們油質的皮膚在水箱的燈管照射下閃著光。接下來是章魚,被網袋裝著,這樣它們縱有八條腿,也不能在淺淺的水箱裏逃跑了。

為了感受日本沿海的生活,我住在三重縣的答誌島上,離它最近的城市——鳥羽市——距離大阪約三小時車程。這個小市場大概只服務島上2500左右的人口,但是當為海產討價還價時,空氣中仍有一絲急切。

就像日本的所有事情一樣,這裏沒有任性,取而代之的是被小心遵守的慣例。我打斷了這天的常規流程,所幸我在的同時還有一場學校的實地考察。當他們繞著水箱奔跑,我則試圖做一個守規矩的打擾者,慢慢地從一個水箱走向另一個,研究這些被陳列出來的魚。

語言障礙意味著了解和學習如何食用這些魚更難了,但隨著拍賣的開始,失望很快就消退了。我住的旅館老板娘參與了這場拍賣,結束時看著今晚將要享用的魚被買下、裝進貨車裏,這讓我興奮異常。菜單上沒有河豚,但是當這天結束,我享受了一頓以鯖魚和其他為主的懷石料理。

Aatish Nath is a freelance food and travel writer based in Mumbai, India. He’s always been fascinated by where our food comes from. An avid photographer, his Instagram can be found at @aatishn. He has a passion for live music and architectural photography.

Aatish Nath 是一位在印度孟买的美食与旅行自由写作者。他一直对我们的食物来源十分感兴趣。同时他也热衷于摄影,Instagram 账号是 @aatishn。Aatishn 对现场音乐和建筑摄影富有激情。