BY DUSTIN GRINNELL

Jet lag, foreign cuisines and crowded trains:

“Traveling and constipation are good bedfellows,”

said no one ever, but should have.

It was my fourth day in Beijing without going number two. That’s four days of breakfast, lunch, dinner, some snacks, some drinks, all backed up and getting weird in thirty feet of cramped intestines. I had experienced backups in my travels, but ninety-six hours was ridiculous.

I was visiting China to carry out a rejected Fulbright/National Geographic fellowship. I had intended to spend nine months studying Traditional Chinese Medicine—a broad range of 2,000-year-old medical practices—but when my proposal didn’t make the cut I told my host advisor, Dr. Peicheng Zhang at the Institute for Materia Medica in Beijing, that I was coming anyway.

By the second day in Beijing, I had adjusted to the deep stares my “blue eyes and yellow hair” were attracting, the city’s frenetic pace, weaving mopeds and flashing stores with staff shouting discounts through headset microphones, but the food still vexed me. The dishes I was eating from curbside vendors were going into my body, but not coming out, dropping into a seemingly bottomless pit of tangled noodles.

I was sightseeing when I felt those got-to-go pangs and scurried for a public bathroom. When I reached a stall, I fumbled with my belt and surveyed my surroundings. There was a sharp, foul odor and a glistening yellow stream at my feet, evidence of poor aim. Near the door was a cylindrical trash can topped-off with dirty toilet paper. Since the plumbing in China isn’t robust enough to transport paper, you don’t flush it, you store it. With everyone else’s. I eyed the trash can and imagined what creatures were bedding down in its filthy ecosystem: parasites, bacteria, Velociraptors.

No, I thought. There will be no pooping today.

You might think my GI tract sent side-splitting pain signals to my brain, forcing a bowel movement, despite my mind’s resistance. Perhaps there was a gaseous ejection, a shot across the bow, if you will? Maybe an accident?

No. My brain and bowels concurred.

And I held it.

With such Zen-like control over my colon, I predicted that I could go days, even weeks without defecating. I might never have to go again, I thought, and continued with my fellowship studies.

My Beijing guide was a soft-spoken medicinal chemist named Ziming who met me at my hostel and taxied us to his lab at the Institute for Materia Medica. Waiting for us in Dr. Zhang’s office were watermelon and grapes, which we munched on before Dr. Zhang, a quiet but brilliant man, joined us to discuss his lab’s research that involved extracting and analyzing natural compounds from medicinal plants and herbs.

After the interview, the three of us joined other postdocs at the communal ping pong table, where Ziming, paddle in hand, told me that he had read my Fulbright proposal and said he would be honored to take me to pharmacies, hospitals, institutes and universities that practiced or studied Traditional Chinese Medicine.

The Zhang lab took me out to dinner for traditional Beijing cuisine later that night. We used hot water to wash our chopsticks and plates, and then the table filled with white rice, vegetables and various meats, followed by the main dish: succulent Peking duck, which was crispy on the outside, juicy on inside, and came with the warning, “Once bitten, forever smitten.”

I spent two more days crisscrossing Beijing with Ziming, visiting Tongrentang, a traditional herbal pharmacy, and then the Hospital of Acupuncture of Moxibustion, where I underwent acupuncture with a traditional doctor.

I said goodbye to the Zhang lab and was waiting for a train in a crowded terminal when I realized that my insides had become bunched-up like the travelers around me vying for exits. I admitted that there was nothing Zen about my perceived control over my bowels. Like everyone else, I was a slave to the meals I had eaten 48 hours prior.

Truth be told, Nature had been calling all along, and I wasn’t going because I was afraid: Of the parasites, the bacteria, the raptors. I knew the constipation had to stop and the train station was my Waterloo.

I hustled into the station’s bathroom, opened a stall door and locked eyes with a Chinese man hovering over a squat toilet. He glanced up from his cell phone, a cigarette dangling from his lips, a blank expression on his face. Oops, sorry. The next stall was vacant and I squeezed my 40-pound backpack into the narrow space.

I hung my pack on the door and frowned at the trash can. As I took a deep breath, I told myself there weren’t prehistoric beasts scratching at the trash can’s interior. I hovered over the squat toilet and reminded myself that the only poop to fear was poop itself.

And I went.

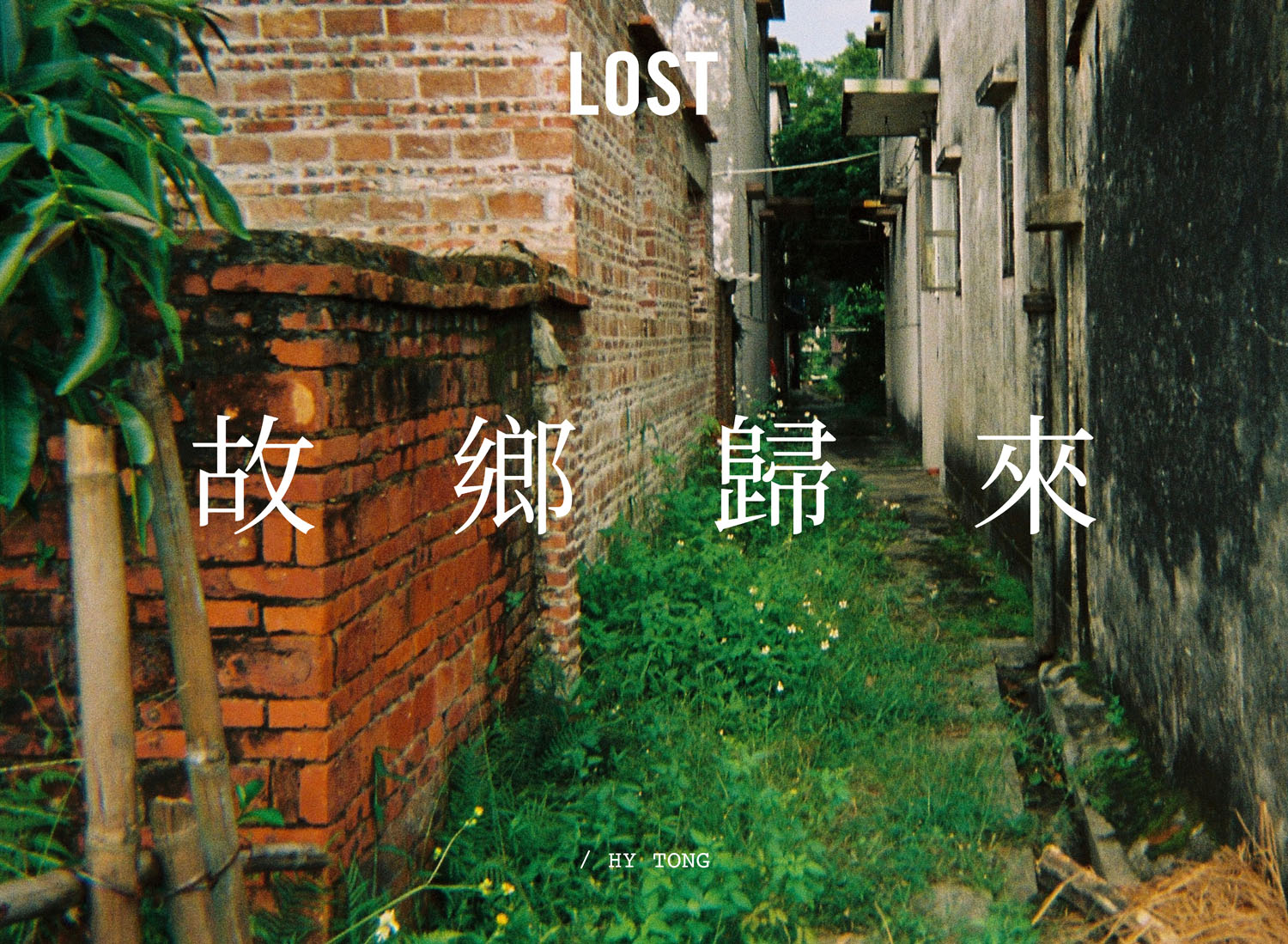

I took a seat on the train, a decidedly lighter human being, and watched the countryside rush by until I arrived five hours later in Xi’an in Central China. As I walked the city’s Muslim Quarter, I thought about Chinese medicine, which is based on the notion of harmony and balance. I had been decidedly out of balance in Beijing – and backed up as a result. Perhaps it was jetlag, or the city’s wild pace, or the stress of the reporting duties I had imposed on myself as a writer. Either way, I was intent on regaining my balance and decided to avoid major cities for the next two weeks. I continued south by train, trading the city’s congested alleyways for the wide open spaces of the Yunnan Province.

In China’s Guangxi region, I avoided a bus from Guilin to Yangshuo, opting instead to float down the Li River on a bamboo raft. On the shuttle bus to the river, I was tapped on the shoulder by Jenny, a third-year college student from the Guangdong province. We chatted through slow, choppy English and became fast friends. We shared a bamboo raft and gazed in awe at the breathtaking karst peaks hugging the tranquil Li River.

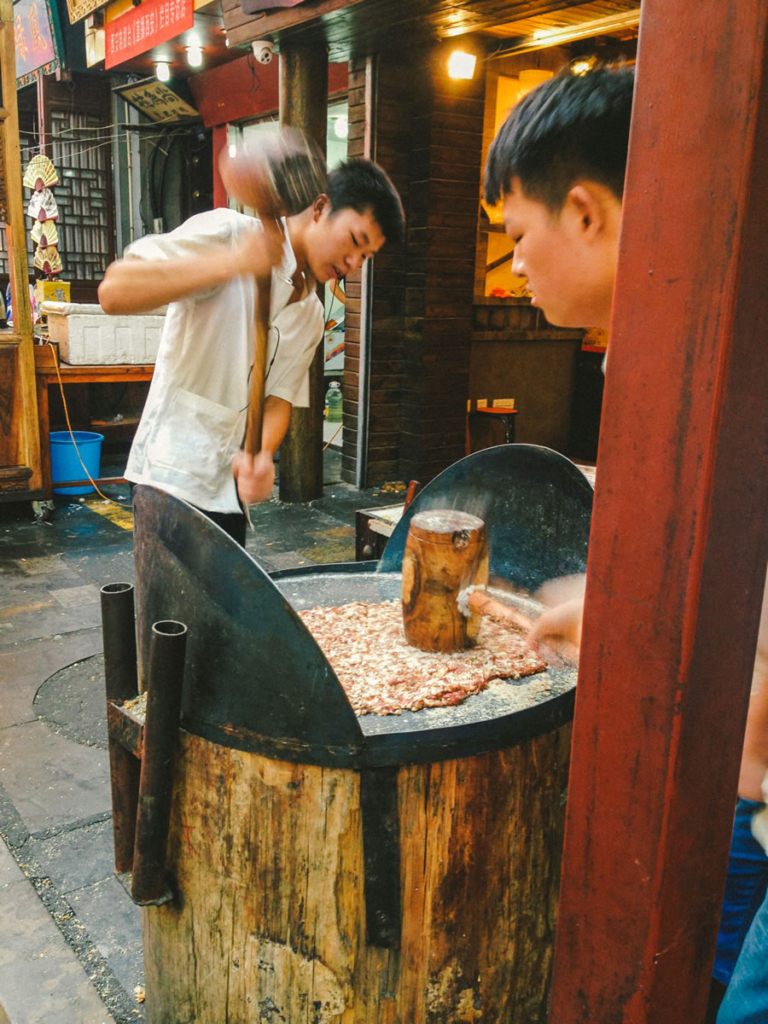

From the raft, Jenny and I watched fishermen snag fish with cormorants. We took pictures atop the 600-year-old Dragon Bridge. Later, we spent the night strolling through the buzzing streets of Yangshuo. My stomach grumbled as restaurant staff hounded us along walkways, pointing at enticing dishes on laminated menus, which displayed main courses of fish stews brewed in spices and vegetables.

“Maybe we take a table?” Jenny offered.

“Absolutely,” I said.

時差、異國食物和擁擠的火車:

“旅行與便秘是很要好的夥伴。”

雖然沒人這麼說,但是應該有人這麼說。

這是我在中國的第四天,還沒有好好地“嗯嗯”。 四天的早餐、午餐、晚餐,還有小食與飲料,全堵在三十英尺長的腸子裏,讓人不舒服。以前的旅行我也時有便秘,但這次在中國連續96個小時的便秘是很誇張的。

在申請富布萊特/國家地理研究員的職位失敗後,我前往中國去完成這一未竟之事。本打算用九個月的時間學習中醫——一門有著兩千年歷史的醫學,但是我的研究計劃並未過關,我聯系了自己在中國的導師——北京藥物研究所的張培成博士,告訴他我還是要來中國。

在北京的第二天,我就已適應因為自己的藍眼睛和黃頭發而招致的諸多好奇目光,城市生活的快速節奏,助動車在道路上的迂回穿行,用耳機麥克風叫賣打折的商家,唯一折磨我的就是食物,路邊攤上的飯,吃下後卻無法消化,就像陷入了無底的食物坑。

在外出旅行時,我感到一陣腹痛,於是疾步趕向公共廁所。找到一處蹲位後便笨手笨腳地解開皮帶,一股刺鼻的臭氣傳來,環視四周,腳邊還有濺出的黃色尿液,明顯是因為尿得不準。門旁的柱形垃圾桶裏塞滿了用過的廁紙。在中國,馬桶的抽水管道一直容易被衛生紙堵住,因此不是直接扔進馬桶沖走它,而是和其他人用過的衛生紙一起被丟棄在垃圾桶裏。我看著那個垃圾桶,想象著在這樣汙穢不堪的生態系統裏生存著的生物:寄生蟲、細菌和迅猛龍。

不,我想。今天應該還是無法大便。

你可能會認為是我的胃腸道向大腦發出了撕裂般疼痛的信號,然後迫使小腸運動,盡管我還有抗拒意識。也許身體曾有過排氣,但這是對排便的暗示,還只是一次偶然現象?

不。我的大腦和小腸最終達成了一致。

我還是忍住了。

結腸在這樣的禪意控制下,讓我有預感自己將會在幾天,甚至在幾周內都不用排便。也許我再也不用排便了,我這樣想著,同時繼續進行我的中醫研究。

我在北京的向導是一位溫文爾雅的藥物化學家,他叫子鳴,我們在我的酒店裏碰面,然後他打車帶我到他在藥物研究所的實驗室。在張博士的辦公室裏等待著我們的是西瓜和葡萄,我們在張博士面前狼吞虎咽。這位沈穩聰慧的男人和我們一起討論著實驗室的研究,如何從藥用植物和藥草中提取與分析天然化合物。

在此之後,我們三人又和幾位博士後打起了乒乓球,子鳴手握球拍,告訴我說他讀過了我的富布萊特論文提綱,並且十分樂意帶我走訪藥房、醫院、大學和其他中醫或者研究中醫的機構。

那日晚從實驗室出來,大家帶我去吃了傳統北京菜。我們用熱水清洗了筷子和盤子,然後點了米飯,蔬菜和各種肉菜,滿滿一桌,接著上來一道主菜:鮮嫩多汁的北京烤鴨。外層表皮酥脆,內層肉質多汁,然後就有了如下提醒:“一口下去,神魂顛倒”。

我和子鳴用兩天的時間走訪了同仁堂,這是一家傳統中藥房;然後是針灸醫院,在那裏我接受了一位中醫的針灸治療。

離開實驗室後,我在擁擠的火車站等待火車,感覺到身體裏的東西正聚攏在一起,像我身邊的遊客一樣,急切地尋找出口。我承認禪意並未控制我的小腸,和其他人一樣,我也受到食物的束縛。

其實,我一直是需要大便的,只是因為恐懼寄生蟲、細菌和迅猛龍而沒有順其自然。我知道我一定不能再便秘下去,而車站就是我的滑鐵盧 。

我急速奔向了車站的洗手間,推開門,看到一個中國男人正在上蹲便,他拿著手機擡頭看了一眼,嘴裏叼著一支香煙,表情茫然。哎呀,真抱歉。另一個蹲位還空著,我背著40磅的背包擠進了狹小的廁所間。

我把背包掛在了門上,對著垃圾桶皺眉。在深吸一口氣後,我告訴自己垃圾桶裏沒有史前怪獸。我蹲下來,提醒自己,唯一恐懼的就是大便。

我成功排便。

我在火車上找到了座位,身體明顯感到輕松許多。窗外的鄉村風景一閃而過,五個小時後,我到了華中城市——西安。我走到這座城市的穆斯林區,想起了中醫,及其和諧與平衡的理念。在北京,我顯然是失衡了,因此才會便秘。這也許是因為時差,或是城市環境的紊亂,或是身為作家日日寫作的責任以及由此帶來的壓力。不管怎樣,我有意再次找到自己的平衡,並決定在接下來的兩周不再去大城市。我繼續乘火車向南行進,離開城市裏擁擠的小巷,到達雲南的開闊天地。

在中國廣西,我避開了從桂林到陽朔的公共汽車,選擇在漓江乘坐竹筏。在去往漓江的專線大巴上,Jenny 拍了拍我的肩膀,她是一位從廣東來的大三學生。我們憑借著緩慢的、無條理的英語交流很快成為了朋友。我們一起坐竹筏,凝望寧靜的漓江,對高聳入雲的喀斯特地貌驚嘆不已。

在竹筏上,Jenny 和我看到了漁夫用鸕鶿捕魚。我們在有600年歷史的龍橋上拍照。夜晚則是在熙熙攘攘的陽朔街道上散步。我的肚子有些餓,此時正好有餐廳服務生招呼我們入店用餐,並將滿是誘人菜肴的菜單展示給我們看,裏面有放了辣椒和蔬菜的燉菜魚。

“我們也許可以找張桌子坐下來。”Jenny 提議。

“當然可以。”我回答說。

Dustin Grinnell is a writer based in Southern California. He enjoys telling true stories with the imaginative flair of fiction. His travel essays have appeared in such publications as Outside Online, The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, The Philadelphia Inquirer, Salon, Travelmag, The Expeditioner, Living Now and Verge Magazine. He is also the author of the sci-fi adventure novels, The Genius Dilemma and Without Limits. You can check out his work at www.dustingrinnell.com, or follow him on Instagram @dustingrinnell.”

Dustin Grinnell 是一位來自南加利福尼亞州的作家。他很喜歡通過小說講故事,天生想象力豐富。他的旅行文字時常刊登在 Outside Online、《波士頓環球報》、《華盛頓郵報》、The Philadelphia Inquirer、《沙龍》、Travelmag、The Expeditioner、Living Now 和 Verge Magazine。他也是一位科幻冒險小說作家,著有 The Genius Dilemma、Without Limits。可登陸 Dustin Grinnell 的個人網站 www.dustingrinnell.com 或者關註他的 Instagram @dustingrinnell,了解他的更多作品。