WITH THANKS TO EXMOOR

BY KATHRYN HATCHETT

We cross the final river of our trek. Not that you could call it a river yet. The winding ribbon carving out a valley for itself is a couple of feet wide and would be shallow enough to walk through on foot without boots. It trickles towards the coast, a riverbed mosaic of smoothed pebbles. Lichen-clad hawthorns grab at my clothes as we ride past. Ghost green lichen dangles from branches damp with the sea fog rolling towards us. Moss splatters the trunk like careless paint, and all around us, the ferns are fading to copper. The heather is hanging on, purple among the fray. The horse is trying too. A few chocolate-scented flowers remain.

We are only twenty minutes from the stables. I know that on a shorter ride, we would canter up the hill as a last hurrah. The ground we’re on squelches, the dry rise before us inviting. But we’ve been riding for three days, covering sixty miles and about sixteen hours in the saddle. We’re tired, and the horses are tired too.

Except they are not as tired as we believe. Beneath me, Chief, a wonderful horse that I admire greatly (as much as he admires himself, which is a lot), is on his tiptoes. His hindquarters are gathering beneath me; his ears are pricked, waiting for someone to say go.

I almost didn’t book this holiday because I was afraid of being homesick, too shy, or unable to survive alone. This is my first solo trip, and I thought I wouldn’t make it off the driveway at home. I sat in the car, unable to start the engine. Suddenly, I was fearful of a drive I’d done many times. Something had convinced me this trip would be negative, despite how much I hoped for it to be something else. Those thoughts seem ridiculous now.

The past three days have been like walking through a dream. But unlike my dreams, nothing went wrong, nobody died, and it didn’t turn into a nightmare where I attend my own funeral. Surrounded by the moors, I am living the life I’m made for. No signal. No work. No nothing. Out here, the soundtrack consists of mud-clad hooves, the odd snort and birdsong.

We’re only a few paces up the normal canter track, and we know better than to speak the word. Even spacing it out and asking, ‘Are we all ready for a C-A-N-T-E-R?’ has the horses flying without skipping a beat. They’d wait if we asked them, but we don’t want to. They’re having fun too.

Then the ride leader speaks, ‘We usually…’

And that’s all I hear.

Chief takes off up the hill as fast as he can. The other horses copying. I was holding the buckle of the reins with one hand, completely unready to canter. But I’m doing it. The wind rushes past my face, taking the sound of my glee with it. The mist we’ve nicknamed the Exmoor Spritzer coats me. It’s salty and fresh as it catches on my lips.

Joy beyond words fills me from top to toe as if a golden light was flooding into my soul. I can almost see the glow as I drop the reins and let my arms go out to the side. Chief’s hoofbeats reverberate through my bones and up the valley, and I can’t help but smile. The pony beneath me, I hope, knows how much I love him. I pat him as we return to walk, hoping a few pats will convey how that experience with him reformed something in me and fixed something that was shaken. I’m reminded that I can ride. I can do things. I am as capable as anyone else. The worries from earlier in the trip drift from my mind. I crave more adventure.

Tears prick in my eyes as I turn to see the others stopped further down the hill. They’re laughing. Hysterically so.

I turn Chief around and walk back down to them. That’s when I noticed a rider covered in mud, courtesy of Chief’s take-off. It’s thick, Exmoor mud, with blades of grass sticking out from it. It’s in her eye, over her nose, and mouth, even in her ear. I laugh, apologise, and then we all laugh some more.

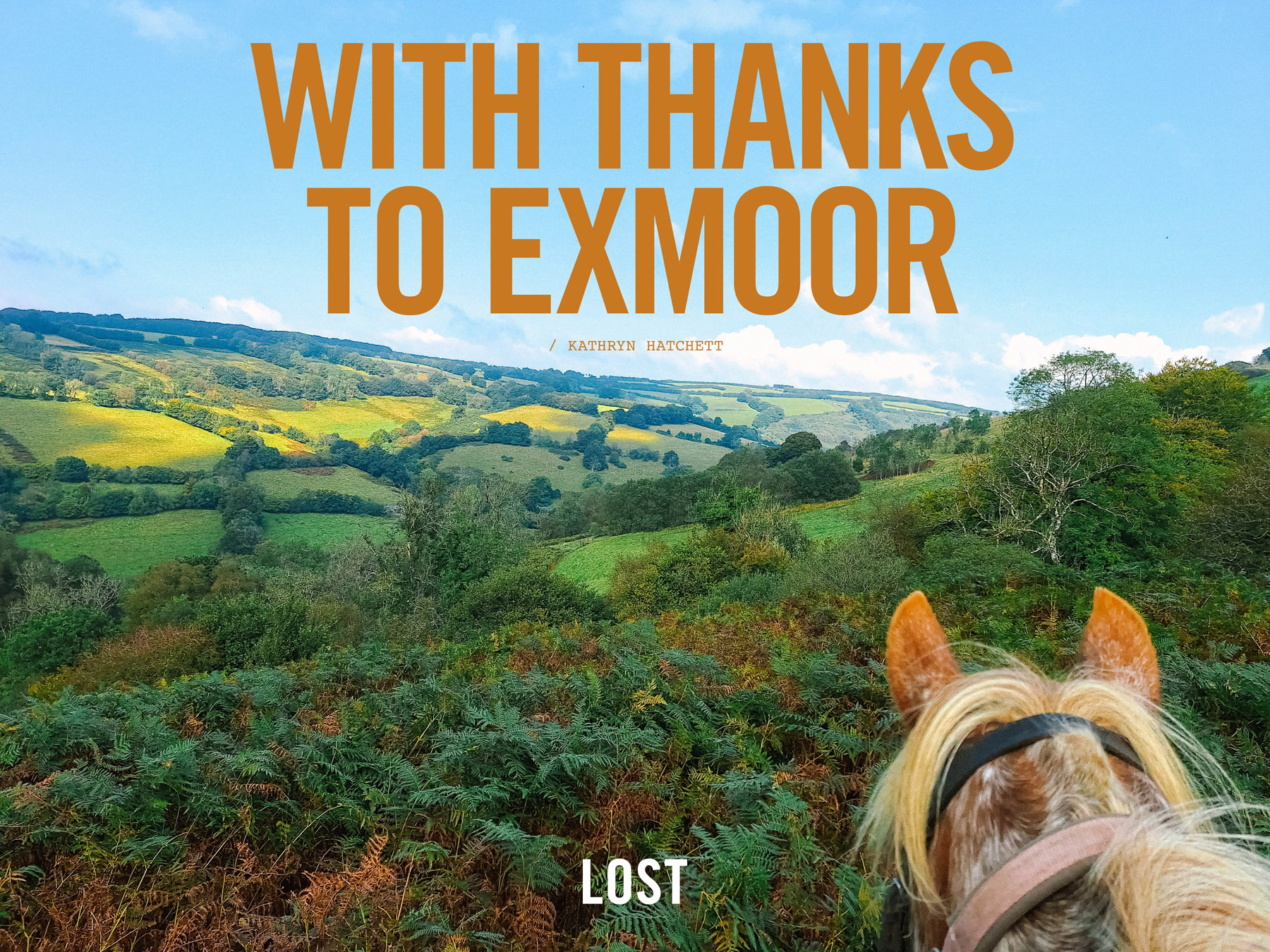

Warmth climbs through my chest and flushes my cheeks. I take this moment in as I try to freeze it in mental keepsakes. My fellow riders. Their horses. The red copper heather valleys behind us, the yellow marsh grass and still-green ferns. The odd tree in the valley beside the stream we’ve wound our way over. The hoofprints in the soft ground memorialising our ride. The sea fog clambering towards us. The low cloud coming down behind us. The skies are grey and miserable; it is all perfect.

Amid the perfectness of it all, the scars stand out. Before the gate into the fields outside the yard is a large hole; a description which doesn’t do it justice, as in truth the hole is not deep, or even that large, but the imprint of a bowl in the ground left by a shell. I recall the Royal Engineers used Exmoor as a training base for experimental chemical warfare during World War Two, and while it isn’t clear in a sweeping glance of the area, there are trinkets of their time here scattered all over. An abandoned cottage sits in a neighbouring valley, a memorial to Colonel R H Maclaren, who was killed in a training accident in 1941. Sometimes, bomb casings are found among the bogs and soil.

The shell crater catches my attention without fault, even though I’ve ridden past it hundreds of times. For something with such a violent beginning, its beauty seems juxtaposed. Lime green ferns climb the sides of the shell hole. Vibrant grass sits at the bottom, sheltered from the harsh winds that blow across from where the Bristol Channel meets the Atlantic.

We cross the road, a tarmac incision through hardy grass and abstract hawthorns. No place is wild anymore.

Once dismounted, I spend a moment hugging Chief, thanking him. He thinks I’m offering myself as a scratching post and almost knocks me flying with his head. I let him whack me with his head as I thank him for being my partner for this trip. It’s more than that, it’s a thanks for helping me to realise I can be independent and push myself without pushing myself over the limit. I stand in the yard for a while, letting him rub his sweaty forehead into me.

Now my feet are on the ground, I am faced with the fact that I travel to ‘wild’ places for peace as we’ve destroyed so many. This wild place serves as a comparison to what we have done to the rest of the planet.

I think of this as I untack Chief, sponge him off, and turn him out. I take my time, drawing out the last echoes of peace within. I stay standing in the field watching the horses roll in mist-coated grass as the fog closes in, freezing this place under its sheet.

KATHRYN HATCHETT is a writer and student living in Somerset. Her writing focuses on the natural world, local history, and mental health. She can often be found exploring hidden-away locations with her border terrier, Jasper, at her heel. Her previous work includes ‘The Handbook’ (Close To The Bone Publishing) and ‘The Downfall of Hummerstone House’ (Every Day Fiction). To join Kathryn on her adventures, you can find her on Instagram @_kathrynhatchett_