THE LONG WAY TO AKTAU

BY BRIENNA CARTER

On the way to the train station, Abdulkhamid told me he failed his English test. We’d spent the last couple days preparing for it, and he’d been nailing the new vocabulary about gift-giving and bag-packing. He could tell you what he’s going to buy his wife for their anniversary (jewelry), and he knew the difference between a wristlet and a clutch (wristlets have straps).

Standardized testing aside, Abdulkhamid’s English was good. Almost all my other conversations in Uzbekistan had been mediated by Google Translate, but Abdulkhamid could talk for hours.

He’d been taking lessons for two years and hosted over a hundred foreign Couchsurfers in his home. But then, at 5am, he was doubting if he was on the right path – if he’d ever get the language certificate, if he’d ever get to Brooklyn’s Little Tashkent. He has my phone number if he ever does.

It was a good few days with Abdulkhamid and his family in Nukus. I went for walks during the day, and in the evening, we drank tea and watched television programs I couldn’t understand. I had a flight the next day from Aktau to Tbilisi though. He’d have to brave the next IELTS chapter alone.

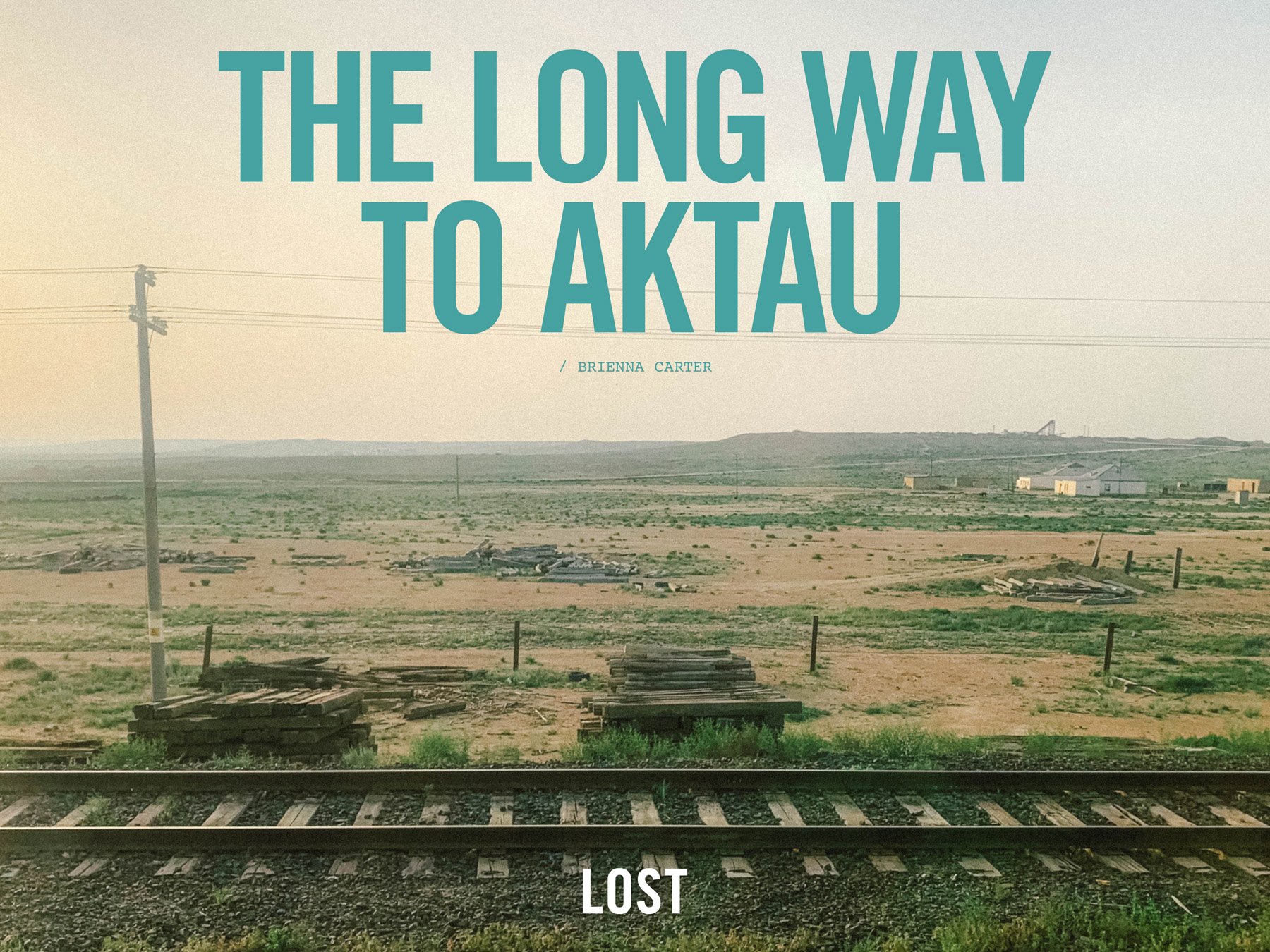

There’s two legs of the train journey: Nukus to Beyneu, Beyneu to Aktau. Altogether, it’s twenty- six hours, with three and a half hours break at the Beyneu station in between. I reserved a ticket in third class but some blogger warned that this doesn’t exactly guarantee you a bed. No one checked my ticket anyway; the berths were all empty anyway. It was cool, and it was quiet, and outside the window, the bazaar was getting set up for the day. Everyone moved slowly, setting out their wares. I’d never seen a bazaar so empty, so calm.

A few hours later, the scene I woke up to in the mid-morning heat was unrecognizable, inside and out. Out the window was endless cracked earth, void except for the power lines running parallel to the train tracks. The inside was full of people, over a dozen per compartment. With so many people it was impossible to use the bunks as beds, so people squeezed three per make-shift bench. Still, there was an overflow that spilt into the walkway.

I spent the morning counting how many utility poles we passed. Somewhere around sixty, I got a tap on the leg. The man tapped, pointed at the bed I occupied, then at an exhausted man to his side. He introduced himself as Yassim and suggested a trade. The tired man sleeps on the top, and I join Yassim and the others sat on the bottom.

My new seat was in between two older ladies dressed in clashing patterns. The patterns and colors clashed with each other’s outfits and also clashed within their own. I learned that they, along with two other women sitting across, were going to Aktau on holiday. We used Google Translate to speak, Russian to English. No one bothers with the Uzbek translations on the app; they’re atrocious.

Everyone was eating food and drinking tea. I’d packed a half-eaten pastry and missed the Bring Your Own Cup memo. One of the men kindly chugged his drink and offered me his mug. It was custom-made, with pictures of a young girl on the outside (a girl I can only assume was his daughter). In one, she’s posing professional portrait-style with her head cupped in her hands, cocked at a slight angle. The other two photos were almost identical selfies.

Yassim ran to the samovar at the back of the car to refresh their teapot, and when he returned, he filled my cup first. Aside from the four women, everyone in the compartment came as strangers. Still, they relinquished whatever food and drink they’d brought to form a compartment stockpile. There was a vegetable mixture and dried fish, torn-apart bits of bread and raspberry jam, a tin of cookies, and a cake made by Yassim’s wife. When Yassim offered me some cake, I felt guilty, knowing this was the last of his wife’s cooking he’d have for months. He was headed somewhere in the Kazakh desert to start a work contract. I asked if his family would visit or if they’d stay in Uzbekistan the entire time he was gone. “No,” he answered, “they’ll stay in Karakalpakstan.”

I asked the others in the compartment where they were from. “You from Kazakhstan or Uzbekistan? Are you coming or going?” “Neither. We are from Karakalpakstan.”

Abdulkhamid, my host in Nukus, was the first to bring up this distinction of Karakalpakstan versus Uzbekistan. He said that Karakalpakstan is in Uzbekistan, but it is not Uzbekistan. That yes, in Nukus they are Uzbek citizens, but they are Karakalpak people. They have their own language and culture, and it’s more similar to Kazakh than Uzbek. Only under the Soviet Union was Karakalpakstan incorporated into Uzbekistan, and it remains as such today.

Theoretically, Karakalpakstan is an autonomous region, but in practice, their government works under instead of with the Uzbeks. Despite taking up 40% of the territory, Karakalpakstan is home to only 6% of the population. The Aral Sea that once dominated the landscape and allowed for agriculture is almost completely dried up by now, leaving desert wasteland behind. Sometimes, the train would briefly stop, and it was in those moments that you could really grasp the enormity of nothingness around.

First, we stopped at the Uzbek border, again at the Kazakh one, and also at some random spots in between. When the train wasn’t in motion, there was no wind, and the temperature became unbearable. Everyone got sweaty, and everyone got bored. At the border crossings, you can’t use your cell phone and you can’t lay on the top bunks. For a bit, I was able to entertain everyone with my American passport. There’s nice pictures of the palm trees in Hawaii and mountains in Colorado. Exchanging my passport with the lady to my right, I learned that her name was Nabir and that she was born the same year as my mom, though I would’ve guessed she was twenty years older.

The Uzbek border control agents came through and stamped no one’s passport, checked only some people’s bags. They didn’t give me a stamp but wanted to have a look at my backpack. They poked around and let the dogs have a sniff. They took a quick glance at my passport and left, just to have the conductor come and grab me fifteen minutes later.

He gestured for me to step off the train, where a lineup of armed guards were positioned at each door. Either I was the only foreigner on the train or they took us out one at a time because the platform was empty save me and the men in uniform. I was brought to a man who asked for my passport and eVisa and asked about my occupation, reason for travel, and age. All of this was secondary to the question he asked first: “Are you married?” Usually, I lie when answering this question. It’s easier to explain why I’m not with my husband than why I don’t have one. There, however, with guns in close proximity, I answered truthfully and received a smile in return.

Back on the train, I told my cabin mates about the encounter and in the process revealed my marital status. Nabir told me she “wanted to marry me.” She wanted to know, “When you marry, will you bring your husband to America?” She had sons my age and was keen to make one of them my husband. Yassim translated this for me, and I joked back to him that if I married Nabir’s son, I’d never leave Uzbekistan. He responded, “No, Karakalpakstan,” as if I’d learned nothing.

Once the train was on the move again, the phones came out and YouTube videos were put on. No one cared to show me Uzbek songs though, only American ones: lyric videos for 50 Cent, Evanescence, and Eminem (Yassim’s favorite). Yassim sang and rapped along without looking at the screen. He looked at me instead. He didn’t need the lyrics. He knows them all by heart. He needed me to know that he knew them by heart. Others hummed along and got a few words in before the Kazakh border agents rounded up everyone’s passports. They set up a makeshift border control booth in the last compartment of the car, though I was the only one who had to visit it. All the other passports were simply stamped and passed back. My cabin mates watched in anticipation as I went through a short questioning and got my photo taken. When I returned to my seat, there was a small celebration as if I’d passed some test.

Upon arrival at the Beyneu transfer station, I said goodbye to Yassim and thanked him. We exchanged contact information, and I promised I’d respond to him when he messages me. I promised to help him with English. I bought a chocolate bar and charged my phone. I assured the inquiring locals that I’m fine, that I know where I’m going.

On that second train Beyneu to Aktau, there was hardly anyone. I fell asleep and woke up to an empty compartment. And when I arrived in Aktau, there was hardly anyone there too. On the beach, one family and some wandering wild dogs. The male members of the family were shirtless, but the women were fully covered. Just like that, they swam. I joined them in the water. With so much smog in the sky, the horizon blurred, the Caspian Sea forever ahead.

BRIENNA CARTER is a writer and researcher from New York, based in Tbilisi. She hates planes and loves hitchhiking. You can read more of her writing on Substack briennacarter.substack.com and contact her via email at briennac4rter@gmail.com.